Tenth Evening – Dũng Sĩ – Warrior – Song ngữ

English: Joseph Goldstein.

Việt ngữ: Nguyễn Duy Nhiên. – Nhà xuất bản: Sinh Thức

Compile: Lotus group.

Tenth Evening – Dũng Sĩ – Warrior

Carlos Castaneda (1925 – 1998) was an American author.

Starting with The Teachings of Don Juan in 1968.

In the books by Carlos Castaneda, Don Juan speaks of the necessity for a man or woman of knowledge to live like a warrior.

Trong sách của Carlos Castenada, Don Juan nói mỗi người chúng ta cần phải sống như một dũng sĩ.

The Teachings of Don Juan: A Yaqui Way of Knowledge was

published by the University of California Press in 1968 as a work of

anthropology, though many critics contend that it is a work of fiction.

The image of being a warrior resonates deeply with the experiences of meditation. A warrior takes everything in life to be a challenge, responding fully to what happens without complaint or regret. What usually matters most to people is affirmation or certainty in the eyes of others; what matters most to a warrior is impeccability in one’s own eyes. Impeccability means living with precision and a totality of attention. What we’re doing in coming to an understanding of ourselves is the noblest thing that can be done. It is the eradication from the mind of greed, of hatred, of delusion; establishing in ourselves wisdom and loving compassion. It’s difficult and rare and requires great impeccability. This does not necessarily entail going off to the Mexican desert or to a cave in the Himalayas. It means, rather, cultivating qualities of mind which bring about totality and wakefulness in every moment.

Hình ảnh một người dũng sĩ rung động sâu xa với kinh nghiệm thiền quán. Người dũng sĩ đối diện với mọi hoàn cảnh của cuộc đời như là những thử thách, anh ta đối phó một cách vẹn toàn mà không bao giờ than van hay hối hận. Theo đa số chúng ta thì giá trị của mỗi người tùy thuộc vào sự phê phán, chấp nhận của những người chung quanh; đối với người dũng sĩ, giá trị nằm ở sự toàn thiện của chính mình. Toàn thiện có nghĩa là sống trong chánh niệm một cách trọn vẹn và tinh mật. Những gì ta đang cố thực hiện ở đây là tự tìm hiểu mình, một điều cao quý nhất mà một người có thể làm được. Công việc này khó, hiếm hoi và đòi hỏi một sự toàn thiện. Nhưng ta không cần phải bỏ nơi này để đi đến một sa mạc hoang vu hay một hang động nào đó trên dãy Hy mã lạp sơn. Ta chỉ cần trau dồi những đức tánh tốt nào có khả năng đem lại cho ta một sự thức tỉnh trọn vẹn trong từng giây từng phút.

Nobel Prize winner Hermann Hesse’s most lauded book:

The enchanting story of one man’s journey in search of enlightenment.

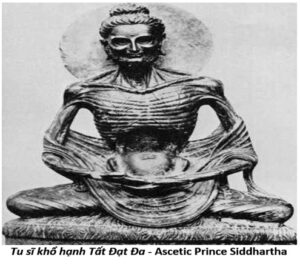

The book Siddhartha by Herman Hesse, describes very beautifully the emergence of a warrior in a context quite different than that of Carlos and Don Juan. Siddhartha said that his training had left him with three powers: he could think, he could wait, he could fast. Three qualities of mind, three characteristics of a warrior. The ability to think in this sense means clarity, not being muddled or confused about what is happening. Clarity with respect to the body—being aware of postures, the breath, the interplay of the physical elements, becoming sensitive to just how much food and sleep is actually needed. Bringing all the different kinds of bodily energies into balance. Clarity with respect to the mind—emotions, thoughts, and different mental states. Not getting caught up in the whirling’s of the mind, staying clear and balanced in their flow.

Trong câu chuyện Siddhartha, Herman Hesse có kể lại một hình ảnh rất đẹp của một người dũng sĩ, hơi khác hình ảnh của Carlos và Don Juan. Trong chuyện này, Siddhartha kể rằng sự luyện tập giúp cho anh có được ba quyền năng: anh có thể suy nghĩ, anh có thể chờ đợi và anh có thể nhịn ăn. Ba đặc tính của tâm, ba đức tính của một dũng dĩ. Khả năng suy nghĩ ở đây có nghĩa là sáng suốt, tỉnh táo, không hoang mang, bối rối về việc đang xảy đến với ta. Trên phương diện thân thể – nó có nghĩa là ý thức được oai nghi, hơi thở của mình, thấy được những động tác của các hiện tượng vật lý, biết điều độ trong sự ăn uống, ngủ nghỉ của mình. Duy trì sự cân bằng giữa các năng lực trong thân. Trên phương diện tâm thức – nó có nghĩa là ý thức được tình cảm, tư tưởng và những trạng thái khác nhau trong tâm. Không bị lôi cuốn theo cơn lốc xoáy của tư tưởng, lúc nào cũng giữ được sự an tĩnh, cân bằng trong tâm mình.

Hermann Karl Hesse (1877 – 1962) was a German-born

Swiss poet, novelist, and painter. Nobel Prize in Literature In 1946.

Another aspect of Siddhartha’s power to think involves courage: not being locked into preconceptions of how things are. Courageous enough to be open and receptive to different possibilities. Siddhartha did not believe blindly. He didn’t believe his friends or parents, not his teachers, nor even the Buddha. He wanted to find the truth for himself, and the courage to do that opened him to a wide range of experience; going into the forest for three years and practicing the ascetic disciplines; having a beautiful love relationship with Kamala, the courtesan; getting involved in the world of business and commerce. He was open and courageous enough to experience and accept all the consequences, and was not made timid by narrow thought distinctions. The power of thinking is the power of clarity and courage—to experiment, to investigate, to probe what’s going on.

Khả năng suy nghĩ của Siddhartha cũng bao giờ gồm cả lòng can đảm: không bị nô lệ vào thành kiến và những cố chấp của mình. Can đảm đủ để cởi mở quan niệm của mình ra để chấp nhận những điều có thể được khác. Siddhartha không bao giờ tin mù quáng vào một điều gì hết. Anh ta không tin ở bạn bè, ở cha mẹ mình, ở các vị thầy hay ngay chính cả nơi đức Phật. Anh muốn phải tự chính mình chứng nghiệm được chân lý, và nhờ động lực này mà anh đã can đảm mở rộng tư tưởng của mình ra khám nghiệm tất cả. Siddhartha đã bỏ vào rừng trong vòng ba năm trời, để tu theo lối khổ hạnh, ép xác, rồi anh ta lại vui sống với Kamala một cô gái giang hồ hạng sang, hoặc tham gia vào chốn thương trường bon chen, lừa lọc. Anh ta lúc nào cũng sẵn sàng và có đủ can đảm để chấp nhận thử thách và bằng lòng với mọi hậu quả. Anh không để những sự phân biệt nhỏ nhoi làm nãn chí mình. Khả năng suy nghĩ bao gồm sự sáng suốt và lòng cam đảm dùng để trực tiếp kinh nghiệm, thăm dò và quán sát những sự việc đang xảy ra.

The courage of a warrior is both required and developed in the practice of meditation. It takes courage to sit with pain, without avoiding or masking it; just to sit and face it totally and overcome one’s fear. It takes courage to probe and by that probing discover the deepest elements of the mind and body. It can be quite unsettling at first because many of our comfortable habits get overturned. It takes a lot of courage to let go of everything that we’ve been holding onto for security. To let go, to experience the flow of impermanence. It takes courage to face and confront the basic and inherent insecurity of this mind-body process. To confront the fact that in every instant what we are is continually dissolving, vanishing; that there is no place to take a stand at all. It takes courage to die. To experience the death of the concept of self; to experience that death while we’re living takes the courage and fearlessness of an impeccable warrior.

Lòng can đảm của một dũng sĩ là một điều cần thiết, cũng như nó sẽ được khai triển trên con đường thiền quán. Ngồi với cơn đau của mình mà không tránh né hay trốn chạy, đòi hỏi một sự can đảm, dám thẳng mặt đối diện với nó để vượt qua nỗi sợ hãi của chính mình. Sự quán chiếu này cần một sự can đảm không nhỏ, nhưng nhờ vậy ta mới có thể khám phá, hiểu được những sự thật sâu xa của thân và tâm mình. Lúc đầu nó sẽ rất là động loạn, vì những thói quen thường ngày của ta bị xáo trộn. Phải can đảm lắm ta mới có thể buông bỏ tất cả những gì mà ta hằng nắm giữ cho sự an ninh của mình. Hãy xả bỏ, để kinh nghiệm được dòng vô thường. Phải có can đảm ta mới dám đối diện và đương đầu với nỗi bất an căn bản và cố hữu của tiến trình thân tâm. Ðể đối diện với sự thật, là chúng ta đang tàn hoại trong mỗi giây phút, không có một nơi nào để ẩn náo. Phải có can đảm mới chết được. Kinh nghiệm về sự chết của cái Ngã; kinh nghiệm được cái chết trong khi mình vẫn còn sống, cần một lòng cam đảm, vô úy của một đại dũng sĩ.

Siddhartha could think and wait and fast.

Siddhartha có thể suy nghĩ, chờ đợi và nhịn ăn.

Emptiness, stillness, tranquility … silence, non-action—

this is the level of heaven and earth. – Chuang Tzu

Waiting means patience and silence. It means not being driven to action by our desires. If we don’t have the ability to wait, every desire which comes into our minds compels us to action and we stay bound on the wheel of craving. Sometimes waiting is misinterpreted as inaction, not doing anything. It’s not that at all. Chuang Tzu wrote:

Chờ đợi có nghĩa là kiên nhẫn và thinh lặng. Nó có nghĩa là không bị lôi cuốn vào hành động chỉ vì lòng ái dục. Nếu chúng ta không có khả năng chờ đợi, mỗi khi ham muốn khởi lên, nó sẽ dẫn đến hành động. Và rồi ta lại bị trôi lăn theo vòng bánh xe của ái dục. Ðôi khi người ta thường lầm lẫn chờ đợi với lại bất động, không làm gì cả. Hoàn toàn không phải như vậy. Trang Tử có viết:

The non-action of the wise man is not inaction. It is not studied. It is not shaken by anything. The sage is quiet because he is not moved, not because he wills to be quiet. Still water is like glass … it is a perfect level. If water is so clear, so level, how much more the spirit of man. The heart of the wise man is tranquil, it is the mirror of heaven and earth, the glass of everything. Emptiness, stillness, tranquility … silence, non-action—this is the level of heaven and earth. This is perfect Tao. Wise men find here their resting place. Resting, they are empty.

Sự bất động của người trí không phải là không làm gì hết. Mà có nghĩa là không tính toán. Nó không bị lay chuyển bởi bất cứ một việc gì. Bậc thánh nhân an tĩnh vì họ không động, chứ không phải vì họ cố ý làm an tĩnh. Nước lặng giống như gương… một mặt phẳng hoàn toàn. Nếu nước thật trong và thật phẳng, thì tâm của bậc thánh nhân cũng thế. Tâm của người trí luôn luôn thanh thản, nó là tấm gương của trời đất, vạn vật. Vắng lặng, an tĩnh, thanh thản… thinh lặng, bất động – đây là lãnh vực của trời đất. Nó chính là Ðạo. Bậc trí tìm nơi đây chỗ an nghỉ cho họ. Khi an nghỉ, họ sống vắng lặng.

Waiting means stillness of mind in whatever the activity. If we are always busy trying to help the Dharma along, it prevents us from seeing clearly, from receiving the strength and understanding that comes out of silence, from stopping the internal dialogue. For as long as the internal dialogue goes on, so long do we remain in a prison of words which keeps us from relating in an open and spontaneous way to the world—a world that’s very different from what our preconceptions lead us to imagine. Stopping the internal dialogue is the ability to wait and to listen.

Chờ đợi có nghĩa là sự tĩnh lặng của tâm, trong bất kỳ một hoạt động nào. Nếu chúng ta cứ lo bận rộn đi “hoằng pháp”, ta sẽ không có được một cái nhìn rõ ràng, ta sẽ không thể nhận được rằng sức mạnh và sự hiểu biết phát sinh từ sự thinh lặng, và nhất là ta sẽ không ngừng được sự đối thoại trong nội tâm của mình, ta sẽ trở thành tù nhân của mớ văn tự, chữ nghĩa. Chúng ngăn chận không cho ta liên lạc với thế giới chung quanh một cách cởi mở và tự nhiên. Thế giới chung quanh khác biệt với những khái niệm và thành kiến của ta nhiều lắm. Chấm dứt những đối thoại trong nội tâm của mình là khả năng chờ đợi và lắng nghe.

It was listening to the voice of his heart which led

Siddhartha from his father to the ascetics, and then from the

forest into a worldly life of business and love.

It was listening to the voice of his heart which led Siddhartha from his father to the ascetics, and then from the forest into a worldly life of business and love. But slowly that quality of listening became jaded by over-indulgence in sense pleasures. He became so involved in his desires that he no longer could hear. Full of despair he dragged himself to the side of a river, and was about to drown himself when he heard from the river, from his heart, the sound of “Aum.” And staying thereby the river for many years he again learned to listen, to wait.

Chính vì nhờ lắng nghe con tim mình, mà Siddhartha đã rời cha mình để đi vào con đường khổ hạnh, và rồi từ giả rừng sâu để trở về với thế giới trần tục của thương mại và tình yêu. Nhưng dần dà sự lắng nghe của anh ta bị trở nên mờ ám vì những đam mê, khoái lạc của sắc dục. Cho đến một lúc anh không còn nghe gì được nữa. Trong sự tuyệt vọng cùng cực, anh ta lê chân đến bên một dòng sông, định tự trầm mình. Lúc ấy anh bỗng nghe từ dưới dòng sông, từ đáy hồn anh, âm thanh “AUM” vang dội. Anh quyết định ở lại với dòng sông. Vài năm sau, anh lại bắt đầu biết lắng nghe và biết đợi chờ.

Siddhartha listened. He was now listening intently, completely absorbed, quite empty. Taking in everything. He felt that he had now completely learned the art of listening. He had often heard all this before, all these numerous voices in the river. But today they sounded different. He could no longer distinguish the different voices, the merry voice from the weeping one, the childish from the manly one. They all belonged to each other. The lament of those who yearn, the laughter of the wise, the cry of the indignant, and the groan of dying. They were all interwoven and interlocked, entwined in a thousand ways. All the voices, all the goals, all the yearnings, the sorrows, the pleasures, all the good and evil, all of them together with the world, all of them together with the stream of events and the music of life. When Siddhartha listened attentively to this river, to this song of a thousand voices, when he did not listen to the sorrow or laughter, did not bind himself to any one particular voice and absorb it into himself, but heard them all, the unity—then the great song of a thousand voices consisted of one word—perfection.

Siddhartha lắng nghe. Chàng bắt đầu chú tâm lắng nghe, miệt mài trong thinh lặng. Chàng hấp thụ tất cả. Chàng cảm thấy rằng, bây giờ mình đã hoàn toàn học được nghệ thuật lắng nghe. Những âm thanh này chàng đã nghe chúng từ xưa, những tiếng gọi khác nhau của dòng sông. Nhưng hôm nay chúng mang một vẻ khác biệt. Chàng không còn có thể phân biệt giữa những tiếng gọi khác nhau được nữa, tiếng vui ca với tiếng than thở, tiếng trẻ thơ với lại tiếng trưởng thành. Tất cả đều lệ thuộc vào nhau. Tiếng than vãn của nhưng ai sầu khổ, tiếng cười vang của người trí tuệ, tiếng khóc la của kẻ phẩn uất và tiếng rên rĩ của người đang hấp hối. Tất cả đều dựa vào nhau, dính chặt, quấn quýt, đan dệt vào nhau trong ngàn đường lối. Tất cả những tiếng gọi, những mục đích, những lời than, những muộn phiền, những niềm vui, mọi điều ác và thiện, tất cả đều hòa hợp lại trong thế gian này, trong dòng biến cố và âm nhạc của cuộc sống. Siddartha miệt mài lắng nghe dòng sông, theo bài ca muôn ngàn tiếng hát, khi chàng không chỉ lắng nghe theo tiếng khóc hay tiếng cười, chàng không chỉ lắng nghe một âm thanh duy nhất nào, nhưng là lắng nghe tất cả, một thực thể đồng nhất – khi bài ca của ngàn tiếng hát tụ hội lại trong một chữ – trọn vẹn.

The third power of Siddhartha was fasting. Fasting means

giving up, renunciation, surrender. It means energy and effort and

strength. Power and lightness of mind come from renunciation.

The third power of Siddhartha was fasting. Fasting means giving up, renunciation, surrender. It means energy and effort and strength. Power and lightness of mind come from renunciation. Often people think that giving things up, or fasting, is a burden and source of suffering, not realizing the joy and simplicity in being unencumbered by unnecessary possessions and incessant desires. There is no super-human effort needed to practice renunciation; the energy required is only to overcome our inertia and old habit patterns. When this effort is put forth, we experience a spaciousness and ease of mind which comes from the letting go of attachments.

Quyền năng thứ ba của Siddhartha là nhịn ăn. Nhịn ăn ở đây có nghĩa là buông xả, từ bỏ, nhân nhượng. Nó cũng có nghĩa là năng lực, tinh tấn và sức mạnh. Sự từ bỏ đem lại cho tâm ta một sức mạnh và sự thanh nhẹ. Phần đông thường cho rằng sự buông bỏ hay nhịn ăn là nguồn gốc của khổ đau, mà quên đi sự an lạc, đơn giản mà nó có thể đem lại cho tâm hồn. Vì lúc ấy ta không còn bị ràng buộc, chi phối bởi những ái dục không cần thiết. Chúng ta đâu cần đến một cố gắng siêu phàm nào mới có thể thực hành được sự từ bỏ. Ta chỉ cần cố gắng vượt qua những lôi cuốn và thói quen thường ngày mà thôi. Khi ta thực hành được điều này, ta sẽ kinh nghiệm được sự thênh thang, tươi mát của tâm hồn mình vì đã từ bỏ được những dính mắc và quyến luyến.

Fasting means simplicity. One of the joys of studying in India, even though there were many difficulties in health and food and living arrangements, was the basic simplicity of life. It was not encumbered by many of the things that burden us in America. Travelers passing through would wonder how we could “renounce” so many things—electricity and hot running water, not understanding the lightness of living so simply. From simplicity of living, from not needing to have or possess so much, come contentment and peace.

Nhịn ăn cũng có nghĩa là sự đơn giản. Một trong những niềm vui khi tôi còn tu tập ở Ấn Ðộ – mặc dù gặp nhiều khó khăn trong các vấn đề sức khỏe, thực phẩm và tiện nghi – là sự giản dị trong cuộc sống của mình. Nó không bị ngăn trở bởi nhiều việc làm ta nhức đầu như ở Hoa Kỳ. Những khách du lịch đi ngang qua thường thắc mắc, không hiểu nổi làm sao mà chúng tôi lại có thể “từ bỏ” được nhiều nhu cầu đến thế – điện, nước nóng, tiện nghi, vì họ không hiểu được sự thoải mái của một đời sống đời sống giản dị. Từ ở sự đơn giản trong cuộc sống của mình, vì không còn chiếm hữu nhiều, dẫn ta đến một sự toại nguyện và an lạc.

Fasting, renunciation. We can experiment with this letting go in our lives through generosity, through establishing ourselves in basic moral restraint, through practicing giving up the things which bind us. Renunciation happens on all levels, not only in our relationships to material objects or people. There is a Taoist phrase “fasting of the heart” which describes the perfection of inner renunciation. Chuang Tzu wrote:

Nhịn ăn, từ bỏ. Chúng ta có thể kinh nghiệm được sự buông bỏ trong cuộc sống của mình qua hành động bố thí, qua việc giữ giới luật, qua sự lìa xa những gì đã hằng trói buộc ta. Vấn đề từ bỏ xảy ra trên nhiều lãnh vực, không chỉ riêng trong sự liên hệ của mình với những người khác hay những vật chung quanh. Ðạo Lão có danh từ “trai tâm” để diễn tả một hoàn toàn trong sự từ bỏ của nội tâm. Trang Tử viết:

Fasting of the heart empties the faculties, frees you from

limitation and from preoccupation. Fasting of the heart be gets

unity and freedom.

The goal of fasting is inner unity. This means hearing, but not with the ear; hearing, but not with the understanding; hearing with the spirit, with your whole being. “The hearing that is only in the ears is one thing. The hearing of the understanding is another. But the hearing of the spirit is not limited to any one faculty, to the ear, or to the mind. Hence it demands the emptiness of all the faculties. And when the faculties are empty, then the whole being listens. There is then a direct grasp of what is right there before you that can never be heard with the ear or understood with the mind. Fasting of the heart empties the faculties, frees you from limitation and from preoccupation. Fasting of the heart be gets unity and freedom.”

Hãy chuyên tâm nhất chí. Ðừng nghe bằng tai, mà nghe bằng lòng. Ðừng nghe bằng lòng, mà nghe bằng khí. Ðiều gì mình nghe, hãy để nó dừng ở ngoài tai, còn lòng thì hợp nhất nó lại. Khí, là cái Hư không để mà tiếp nhận sự vật. Chỉ có sự trống không mới nhận được Ðạo mà thôi. Sự trai tâm có nghĩa là làm trống không mọi quan năng, tự do, không còn bị giới hạn và bận tâm. Trai tâm sanh nên sự chuyên tâm nhất chí và tự do.

Siddhartha could think. He could wait. He could fast. These are the qualities of a warrior which are developed in coming to understanding the totality of oneself. When you sit, when you walk, when you are impeccably aware all day long, these are the qualities which are being awakened.

Siddhartha có khả năng suy nghĩ. Anh ta có thể chờ đợi. Anh ta có thể nhịn ăn. Ðây là những đặc tính mà một dũng sĩ sẽ khai triển, khi anh ta ý thức được một cách toàn vẹn con người của chính mình. Khi bạn ngồi, khi bạn đi, khi bạn luôn luôn hoàn toàn có ý thức trong một ngày, đây là những đặc tính của sự giác ngộ.

*** *** ***

Question: Don Juan speaks of personal power. How does this relate to practice?

Hỏi: Don Juan có nói về quyền năng của cá nhân. Ðiều này có liên hệ gì đến sự tu tập?

Answer: Strength of mind is power. Not the power which extends itself to manipulate, but the power of penetrating insight, the power to understand. Don Juan said that even if one were told the deepest secrets of the universe, they would appear as just empty words until there was enough personal power. What this power means is strength, steadiness, the ability to penetrate deeply into how things are happening. It develops as the mind becomes more concentrated. From penetrating power comes insight; with strength of mind a single word is enough to open new levels of understanding. In a meditation retreat it is the continuity of practice which develops this kind of personal power.

Ðáp: Sức mạnh của tâm chính là quyền năng. Không phải một quyền lực dùng để sai xử một cái gì bên ngoài, mà là quyền lực của trí tuệ thông suốt, của sự hiểu biết. Don Juan có nói rằng dù cho nếu anh có được nói cho nghe bí mật của vũ trụ này, nó cũng sẽ là rỗng tuếch đối với anh, cho đến khi nào anh có được đầy đủ quyền năng của mình. Quyền năng ở đây có nghĩa là sức mạnh, sự kiên trì điều đặn, khả năng quán chiếu và thấy được chân tướng của sự vật. Quyền năng này sẽ khai triển khi định lực của ta gia tăng. Khả năng quán chiếu sẽ đem đến trí tuệ. Với sức mạnh của tâm linh, một chữ thôi cũng có thể mở ra cho ta một trình độ hiểu biết mới. Trong những khóa tu như vầy thì chính sự thực hành đều đặn, liên tục sẽ làm phát triển loại quyền năng cá nhân đó.

Question: Are there any clear signs along the way that distinguish intuition and insight from imagination?

Hỏi: Có dấu hiệu nào trên con đường tu tập giúp ta phân biệt được trực giác, trí tuệ với lại sự tưởng tượng không?

Answer: Intuitions come out of the silent mind; imagination is conceptual. There’s a vast difference. That’s why the development of insight does not come from thinking about things, it comes from the development of a silence of mind in which a clear vision, a clear seeing, can happen. The whole progress of insight, the whole development of understanding, comes at times when the mind is quiet. Then a sudden, “Aha, that’s how things are!” In the Zen teachings of Huang Po, it talks about insight as being a sudden, wordless understanding. That kind of intuition has a certainty about it because it’s not the product of some thought or image but rather a sudden clear perception of how things are.

Ðáp: Trực giác phát xuất từ một nội tâm tĩnh lặng, còn tưởng tượng là thuộc về những khái niệm. Hai cái đó khác biệt nhau nhiều lắm. Ðó là lý do vì sao mà sự phát triển trí tuệ không bao giờ đến bằng sự suy nghĩ về sự vật. Nó chỉ đến bằng sự tu tập một nội tâm im lặng, để từ đó mà một cái nhìn, một cái thấy sáng tỏ có thể xảy ra. Tất cả mọi phát triển của trí tuệ, của sự hiểu biết chỉ xuất hiện vào những khi tâm ta im lặng. Rồi bất ngờ: “À, thì ra sự thật là như vậy!” Trong truyền thống Zen của thiền sư Hoàng phố, ông có nói về giác ngộ như là một sự hiểu biết đột ngột, thoát ra khỏi mọi ngôn từ. Những trực nhận ấy có một giá trị đặc biệt, vì nó không phải là sản phẩm của óc suy nghĩ hay tưởng tượng mà là một sự vỡ lẽ bất ngờ, đột nhiên thấy được chân tướng của sự vật.

Question: In practice, how is using the mind to probe and investigate related to choiceless awareness?

Hỏi: Trong sự tu tập, việc sử dụng tâm để thăm dò, quan sát một đối tượng và việc ý thức mà không cần chọn lựa một đối tượng nào, liên hệ với nhau ra sao?

Answer: Many ways of developing insight use a direct awareness. We can direct the attention toward various aspects of the process, such as posture, or bodily sensations, or thoughts, as a way of probing specific areas. But even a directed awareness, once it is settled on an area, is really choiceless. Then it’s sitting back and watching what’s happening, without judging, without clinging or condemning. Sometimes people are very timid in their practice, always looking for the rules of how to do it, afraid to make a mistake. Insight comes from mindfulness, and either we’re aware of what’s happening or not. There’s no way of being mindful wrong. Exercise the mind, exercise this probing quality. Be deeply watchful of how thoughts arise out of nothing and pass away into nothing. Or probe into a pain, get on the inside of it. Exercise the mind in a fearless way, not thinking about things, but with silent awareness. The mind can become very malleable. If you work a piece of clay in making pottery, it becomes soft and easily shaped. When the awareness and concentration are developed, the mind also has that kind of workability and flexibility.Explore all aspects of the mind-body process. When I was in India, I lived on the second floor of an ashram. I used to go up and down the steps many times a day, each time exploring the mechanism of climbing a step, how the knee has to work, how the weight shifts. It’s an interesting process. In all of the activities there should be that kind of interest. Seeing, exploring how things are happening. And at other times it’s just sitting back and doing nothing, a choiceless awareness, watching the natural unfolding.

Ðáp: Có nhiều phương pháp phát triển trí tuệ bằng cách chọn một ý thức có đề mục. Chúng ta có thể tập trung sự chú ý vào các mặt khác nhau của tiến trình, như là oai nghi của thân thể, cảm thọ nơi thân hay tâm thức của mình. Chọn đối tượng như là một phương tiện để khám sát một lãnh vực đặc biệt nào đó, thì rồi nó cũng trở thành một ý thức không có sự chọn lựa. Khi ấy hành giả chỉ ngồi yên quan sát và ghi nhận những gì đang xảy ra mà hoàn toàn không phê phán, quyến luyến hay ghét bỏ. Ðôi khi hành giả quá tĩ mĩ trong sự tu tập, cứ luôn tìm kiếm một quy luật để theo, sợ thực hành sai. Trí tuệ phát xuất từ sự chánh niệm và tỉnh thức, cho dù ta có ý thức được điều ấy hay không. Không bao giờ có chuyện chánh niệm “sai” hết. Hãy đào luyện tâm mình, đào luyện đức tánh quan sát khám phá này. Hãy nhìn cho thật sâu xa, để thấy được tư tưởng của mình sinh lên từ chỗ trống không rồi tàn hoại vào chỗ trống không. Còn khi quán sát cái đau, phải dám trực diện nó. Thực tập với một thái độ vô úy, không sợ hãi, không suy nghĩ về một điều gì, chỉ bằng một ý thức im lặng. Tâm ta có thể uốn nắn được rất dễ dàng. Cũng như một miếng đất sét dùng để làm chén bát, nó rất mềm dẻo và nhồi nắn được. Khi ý thức và định lực của ta phát triển, tâm ta sẽ có được tính cách uyển chuyển và dễ vận dụng như thế. Hãy thám hiểm tất cả mọi khía cạnh của tiến trình thân tâm. Khi tôi còn ở Ấn Ðộ, tôi sống tên tầng thứ hai của một tu viện. Mỗi ngày tôi thường đi lên xuống thang lầu nhiều lần, những khi ấy tôi hay quan sát cử động máy móc của động tác bước lên từng bực thang, đầu gối tôi chuyển động ra sao, sức nặng của tôi dời đổi như thế nào. Nó là một tiến trình rất ngộ nghỉnh. Mọi sinh hoạt khác của ta cũng cần phải được chú tâm theo dõi kỹ càng như vậy. Và cũng có những lúc ta ngồi lại và không làm gì hết, ý thức mà không cần chọn lựa một đối tượng nào, quan sát những biến chuyển tự nhiên.

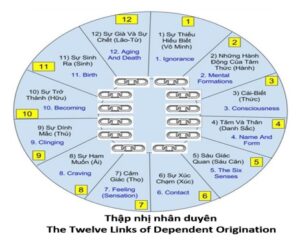

Question: How did this whole process of mind and body all begin?

Hỏi: Cái tiến trình thân và tâm này, nó bắt đầu từ lúc nào?

Answer: There’s a story of a man who was shot by a poison arrow. His friends came with a doctor and wanted to remove the arrow and treat the wound. But the man said, “No, you can’t take it out, I have to know who shot the arrow and where he came from and from what kind of a tree the shaft for the arrow was made and what kind of bird feathers are at the end of the arrow.” Certainly, that man would die before he could get an answer to all thosequestions. In the same way, the Buddha said that a lot of philosophical speculation about the origin of the world, the origin of the universe, about how it all started, is like that man who’s been shot with the poison arrow. We find ourselves in a certain predicament; the predicament is one of being a mind-body that is often full of anger and greed, ignorance and pain. The task is to take the arrow out, to free the mind from those qualities, to free ourselves from suffering. The questions which are most relevant are those which apply to what we are experiencing right now.

Ðáp: Có một câu chuyện về người bị bắn một mũi tên có tẩm thuốc độc. Bạn anh ta gọi một vị thầy thuốc đến để nhổ mũi tên ra và chữa trị cho anh. Nhưng anh lại nói: “Khoan đã, ông đừng lấy nó ra vội. Tôi muốn biết ai đã bắn mũi tên này, người ấy từ đâu đến, mũi tên ấy làm bằng thân cây gì, đuôi của nó là lông của loài chim nào, màu sắc ra sao…” Lẽ dĩ nhiên người ấy sẽ chết trước khi anh ta được trả lời thoả mãn cho những thắc mắc ấy. Cũng vậy, đức Phật cho rằng những câu hỏi triết học về nguồn gốc vũ trụ, của thế giới, vì sao nó lại bắt đầu… thì cũng giống như những câu hỏi của người bị tên độc kia. Chúng ta đang bị kẹt trong một tình thế bất an, tình thế của ta là một hiện tượng thâm tâm luôn bị chi phối bởi những tham, sân, si và đau khổ. Phận sự của ta là nhổ đi mũi tên độc ấy, giải thoát tâm mình ra khỏi những tính chất khổ đau kia. Những câu hỏi có giá trị là những câu hỏi có thể áp dụng vào những gì ta đang kinh nghiệm ngay trong giờ phút này.

Question: Why does greed arise?

Hỏi: Tại sao tham dục lại khởi lên?

When we see something pleasant, we want to hold on,

not understanding the impermanence of it all.

Answer: When we see something pleasant, we want to hold on, not understanding the impermanence of it all. As soon as we become mindful, paying attention to what’s happening, seeing how everything is arising and passing away, the grasping and greed decreases. There’s nothing to hold onto. It’s all bubbles. And the experience of impermanence, the dissolving of the solidity of everything, brings about the letting go, the state of non-attachment. It all comes about through being aware, through being impeccable. It’s inspiring to become a warrior. There’s no one else who can do it for us. We each have to do it for ourselves. Be aware, moment to moment, paying attention to what’s happening in a total way. There’s nothing mystical about it, it’s so simple and direct and straightforward; but it takes doing. That’s what the meditation is all about.

Ðáp: Khi chúng ta tiếp xúc với những vật gì vừa ý, ta muốn bắt giữ, mà không hiểu rõ tính chất vô thường của chúng. Vừa khi chúng ta có chánh niệm, chú ý đến những gì đang xảy ra, thấy được sự sanh diệt của mọi vật, thì lòng tham dục, nắm bắt sẽ giảm đi. Chẳng có gì để ta nắm giữ hết. Tất cả chỉ là bong bóng nước. Kinh nghiệm được lý vô thường, sự tàn hoại của mọi vật, sẽ đưa ta đến sự buông bỏ, một trạng thái không dính mắc. Tất cả đều có được nhờ ở chánh niệm, nhờ ở sự toàn vẹn của chính ta.

Sources:

Tài liệu tham khảo:

- https://theravada.vn/ba-muoi-ngay-thien-quan-loi-mo-dau/

- https://tienvnguyen.net/images/file/lHJ4Mqq01wgQAPRx/30-ngaythienquan.pdf

- https://www.tienvnguyen.net/images/file/8hKjNaq01wgQAKJW/the-experience-of-insight.pdf

- Photo 2: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Carlos_Castaneda

- Photo 3: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Teachings_of_Don_Juan

- Photo 4: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Siddhartha_(novel)

- Photo 4a: https://quotesgram.com/kamala-siddhartha-quotes/

- Photo 5:https://me.me/t/lao-tzu/quotes/riwEZcRb4z7R/

- Photo 6: http://evdhamma.org/index.php/buddhist-study/buddhist-study-3/item/395-bai-so-7-cuoc-gia-tu-vi-dai-song-ngu

- Photo 7: http://evdhamma.org/index.php/dharma/dharma-lessons/item/180-19-lam-sao-de-biet-mot-vi-a-la-han-song-ngu

- Photo 8: http://www.mondaymorningmindfulness.net/2019/06/listening-with-heart.html

- Photo 9: http://evdhamma.org/index.php/dharma/dharma-lessons/item/175-14-thap-nhi-nhan-duyen-song-ngu