Chương 11 – Nhân Duyên Che Án Tam Tướng – Conditions That Obscure The Three Characteristics – Song ngữ

Vipassanā Bhāvanā – Mind Development through Insight

Minh Sát Tu Tập

English: Achaan Naeb Mahaniranonda- Boonkanjanaram Meditation Cente

Việt ngữ: Tỳ kheo Pháp Thông, Tỳ Kheo Thiện Minh

Compile: Lotus group

Chương 11 – Nhân Duyên Che Án Tam Tướng – Conditions That Obscure The Three Characteristics

1.11 CONDITIONS THAT OBSCURE THE THREE CHARACTERISTICS

1.11 NHỮNG ÐIỀU KIỆN LÀM LU MỜ TAM TƯỚNG

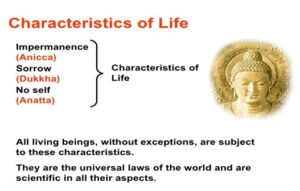

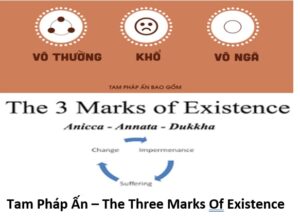

The Three Characteristics refer to impermanence, suffering, and not-self in rupa and nama at all times. But we cannot easily see the Three Characteristics in our own body and mind. Why? Because they are obscured by certain conditions.

Ba đặc tính luôn luôn được đề cập đến là vô thường, khổ đau và vô ngã trong danh pháp và sắc pháp. Nhưng chúng ta không dễ dàng nhận thức rõ ràng tam tướng trong thân và tâm. Tại sao? Vì chúng bị những điều kiện nào đó làm lu mờ.

1) Impermanence. The condition that hides the truth of impermanence (anicca) in the body/mind is santati, or continuity. The rapid sequence of the arising and falling away of rupa and nama give the appearance of a continuous matter, which is, in truth, forming and reforming every moment.

- Vô thường: Ðiều kiện làm cho người ta không thấy được chân lý vô thường (anicca) trong thân-tâm là sự liên tục (santati). Sự liên tục sanh diệt của danh và sắc tạo ra sự kiện liên tục nằm ở trong chân lý, sự hình thành của một khoảnh khắc sát na.

2) Suffering.What hides the truth of suffering (dukkha) in the body is being unaware of what posture the body is in.

- Khổ: Những gì che đậy khổ đế trong thân là không nhận biết tư thế trong thân là gì.

3) Not-Self. What hides the truth of not-self (anatta) in the body/mind is ghanasanna―perception of compactness.

- Vô ngã: Những gì che đậy chân lý vô ngã (anatta) trong thân tâm là ý niệm vững chắc- ghanasana.

How can we “see through” these three conditions in practice?

Làm thế nào chúng ta có thể “thấy rõ bản chất” của tam tướng này trong khi tu tập?

1) Continuity (santati) – Sự liên tục (santati).

Sự sanh diệt của Danh-Sắc diễn ra rất nhanh.

The arising and falling away of rupa and nama is so rapid, it is difficult to see, and so it creates the effect of one continuous body/mind. It is like a movie on a screen which appears to be continuous, but is actually made up of many separate still-pictures. Thus, rupa and nama appear to be substantial and permanent because we can’t see the truth of a rising and falling away. [1] We can’t eliminate this rapid decay (it is the truth), but the yogi must practice with earnestness (seriousness) and awareness until Vipassana wisdom occurs, which will show the separation between the moment of rising and falling. This wisdom will eliminate the continuity (santati) that hides the impermanence of nama and rupa.

Sự sanh diệt của Danh-Sắc diễn ra rất nhanh, khó có thể nhận ra, vì thế nó tạo cho ta cái ấn tượng về một thân – tâm liên tục. Cũng giống như các hình ảnh trên màn hình xi-nê, chúng có vẻ như sinh động, liên tục, nhưng thực sự là được tạo ra bởi những bức hình tĩnh, tách biệt. Danh và sắc cũng vậy, có vẻ như là một thực thể thường hằng, bởi vì chúng ta không thấy được thực trạng sanh diệt [1] của chúng. Chúng ta không thể chấm dứt được sự suy tàn nhanh chóng này (vì nó là thực tánh), tuy nhiên hành giả cần phải thực hành với sự nhiệt tâm và tỉnh thức cho đến khi tuệ minh sát nảy sanh. Chính tuệ này sẽ chỉ cho hành giả thấy được sự tách biệt giữa những chuyển động sanh – diệt ấy. Trí tuệ này sẽ diệt ảo tưởng về tính tương tục che án thực tánh vô thường của Danh-Sắc.

Impermanence can be seen in rupa by cinta wisdom, whereas nama is more subtle, and is difficult to see. When changing, for example, from sitting rupa to standing rupa we can see that sitting rupa is impermanent. That is why the yogi with weak wisdom should practice with kayanupassana Satipatthana (body mindfulness).

Thực tánh vô thường có thể được nhận ra trong sắc bằng tuệ thẩm nghiệm (cintā- paññā), trong khi danh vi tế hơn và rất khó nhận ra. Chẳng hạn, khi thay đổi từ sắc ngồi qua sắc đứng, chúng ta có thể thấy rằng sắc ngồi là vô thường. Đó là lý do tại sao hành giả trí tuệ yếu nên thực hành pháp niệm thân trong Tứ Niệm Xứ (Mindfulness of the body – Kāyanu-passana satipatthanā).

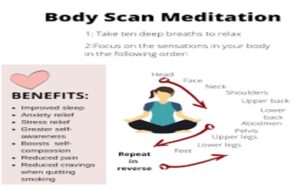

The yogi with weak wisdom should practice with kayanupassana Satipatthana (body mindfulness).

2) Unawareness of Posture – Không tỉnh giác với oai nghi:

Thực tánh khổ bị che án do không biết các oai nghi.

Being unaware of the body posture, we are hence unaware that it is suffering (dukkha). Dukkha means inability to maintain the same condition. (This is sabhava: the true state of the nature. It cannot be changed.) When a position is changed there is dukkha vedana in the old position but lack of “yoniso” in the old position prevents yogavacara from working and seeing the dukkha vedana.

Thực tánh khổ bị che án do không biết các oai nghi. Do không biết các oai ngh icủa thân nên chúng ta không biết rằng nó là khổ. Khổ ở đây có nghĩa là không có khả năng duy trì mãi một điều kiện nào đó (đây là thực tánh pháp, không thể đổi khác được). Khi một oai nghi được thay đổi do có thọ khổ ở oai nghi cũ, nhưng do thiếu tác ý chân chánh (yoniso) nơi oai nghi cũ nên đã ngăn cản không cho chánh niệm — tỉnh giác hoạt động để thấy thọ khổ này.

[1] Of course, the birth and decay of matter and mental states (nama-rupa) is much faster than the frame in a motion picture ―in the magnitude of thousands.

But when yogavacara is observing the position continuously, yoniso will work to prevent defilement, and like and dislike will not occur, and so the yogi will see dukkha vedana in every old position; hence, the new position won’t be able to hide the truth of suffering anymore. For example:

Nhưng khi [chánh niệm — tỉnh giác quán sát] (ba danh) oai nghi liên tục, tác ý chân chánh (yoniso) sẽ làm việc để ngăn tâm phiền não, vì thế, tham sân không thể khởi lên, hành giả sẽ thấy thọ khổ trong mỗi oai nghi cũ. Vì vậy, oai nghi mới không thể che khuất thực tánh khổ đó được.

In sitting rupa, when pain occurs, if there is no “yoniso”, we will think “we” suffer and dislike will occur, and then yogavacara can’t work, and this creates domanassa: the old position is disliked. The yogi stands up because he wants to stand, and abhijjha (liking) occurs for the new position. Now, dukkha vedana can’t be realized in the old position, because the new position hides the dukkha in the old. (This is a good example of how unawareness of posture hides suffering.)

Trong sắc ngồi, khi đau nhức phát sanh, nếu không có tác ý chân chánh, chúng ta sẽ nghĩ rằng “Ta” khổ và sân sẽ nảy sanh, chánh niệm — tỉnh giác không hoạt động nữa, điều này khiến ta không thích oai nghi cũ. Hành giả liền đứng dậy, bởi vì muốn đứng, và tham phát sanh đối với oai nghi mới. Chính vì oai nghi mới che khuất cái khổ ở oai nghi cũ này mà chúng ta không thể nhận ra thọ khổ trong oai nghi cũ. (Đây là thí dụ điển hình cho thấy việc không biết oai nghi sẽ che khuất khổ như thế nào.)

Dukkha vedana in the old position is usually very easy to see when yogavacara is working; but sankhara dukkha (pain carried into the new position) is very difficult to see ―because the new position usually appears to be a happy one. If the yogi is to realize dukkha in the new position, he must have “yoniso”, because tanha or abhijjha (liking) usually occur in the new position ―and domanassa (dislike) occurs in the old position.

Thọ khổ trong oai nghi cũ thường rất dễ nhận ra khi chánh niệm — tỉnh giác làm việc, song “hành khổ” (sankhāra-dukkha — cái đau được đưa vào oai nghi mới) lại rất khó nhận ra, bởi vì oai nghi mới thường có vẻ như là một thọ lạc. Nếu hành giả muốn nhận ra cái khổ trong oai nghi mới, hành giả phải có tác ý chân chánh, bởi vì ái (tanhā), hay sự ưa thích (abhijjha) thường nảy sanh trong oai nghi mới và sự không thích hay ghét (domanassa) nảy sanh ở oai nghi cũ.

Tanha likes sukha (pleasure) and doesn’t like dukkha; so to eliminate tanha there is only one way: the Vipassana wisdom that realizes dukkha. Therefore, the Lord Buddha described wisdom stages that will eliminate tanha, by realizing dukkha.

Ái thích lạc và không thích khổ; vì thế, muốn diệt ái chỉ có một cách duy nhất là phải có Tuệ Minh Sát để nhận rõ khổ. Bởi lẽ đó, Đức Phật đã mô tả những giai đoạn tuệ sẽ diệt được tham ái, bằng sự chứng thực khổ.

Dukkha in practice must be realized four ways:

Khổ trong pháp hành phải được chứng thực bằng bốn cách:

1) See dukkha vedana in the old position;

2) See sankhara dukkhawhen changing to the new position;

3) See dukkha lakkhana (that rupaand nama are anicca, dukkha, and anatta) until separation of santati (continuity) is realized in the 4thyana―Udayabbuyanana.

Then, 4) realize dukkha-sacca in the 11th yana―Sankharupekkhanana. This latter is very strong wisdom, and leads to the 12th yana―Anulomanana(realizing the Four Noble Truths).

1) Thấy thọ khổ (dukkhavedanā) trong oai nghi cũ.

2) Thấy hành khổ (sankhāradukkha) khi chuyển sang oai nghi mới.

3) Thấy khổ tướng (dukkhalakkhana), tức thấy Danh-Sắc là vô thường, khổ và vô ngã — cho đến khi sự tách bạch của tương tục tính (santati) được chứng nghiệm ở Tuệ thứ tư — Sanh Diệt Tuệ (udayabbayañāṇa).

4) Chứng ngộ khổ đế (dukkhasacca) ở Tuệ thứ mười một — Hành Xả Tuệ (sankhārupekkhāñāṇa). Đây là Trí Tuệ rất mạnh, nó dẫn đến Tuệ thứ mười hai — Thuận Thứ Tuệ (anulomañāṇa), chứng ngộ Tứ Thánh Đế.

If the practice doesn’t realize dukkha with wisdom (insight), it is not the right practice, not the Middle Way (i.e., Eight-Fold Path). Only realizing dukkha can lead you out of samsara-vata (wheel of rebirth) ―because realizing dukkha leads to disgust (nibbida) in the Five Khandhas and leads to the end of suffering.

Nếu pháp hành không dẫn đến sự chứng ngộ khổ với trí tuệ, đó không phải là pháp hành chân chánh, không phải là Trung Đạo (tức Bát Thánh Đạo). Chỉ có chứng ngộ khổ mới dẫn ta ra khỏi vòng luân hồi (samsāravatta), nó sẽ dẫn đến sự yếm ly (nibbidā) trong năm uẩn và đưa đến sự đoạn tận khổ.

If the nibbida-yana (8th yana) is not realized, viraga (detachment: absence of lust, absence of desire) will not be realized, and suffering can’t be ended. When it is realized by wisdom that rupa and nama are impermanent, suffering, and without self, disgust will be felt with the suffering of rupa and nama. That is the path of purity.

Nếu không chứng Tuệ thứ tám — Yếm Ly Tuệ (nibbidāñāṇa), thì cũng không thể ly dục (virāga — vắng mặt các dục, vắng mặt tham ái), và dĩ nhiên khổ không thể đoạn tận. Khi, bằng trí uệ, hành giả chứng thực rằng Danh-Sắc là vô thường, khổ và vô ngã, hành giả sẽ cảm thấy chán nản (yếm ly) đối với cái khổ của Danh và Sắc. Đó là con đường thanh tịnh.

Therefore, the practitioner has to have the right “yoniso” in order to realize dukkha in the new position. He must also know the reason for change every time the posture is changed, what benefit there is from correct change with yoniso (so vipassana wisdom can arise), and what penalty if change is not made (defilement will enter). Usually, the new practitioner doesn’t understand the reason for changing the position. He thinks that he wants to change, when in fact dukkha forces the change. When the correct reason is understood and this is repeated over and over, he will see dukkha and realize that the new position is no better than the old. So, liking (abhijjha) will not occur with the new position and dislike (domanassa) will not occur with the old. And this will lead to the wisdom that all rupa and nama are out of control, not self, not man, not woman ―and this is sabhava: the true state of the nature.

Vì vậy, hành giả phải có tác ý chân chánh để nhân ra khổ trong oai nghi mới. Hành giả cũng phải biết ý do tại sao phải thay đổi oai nghi; thay đổi oai nghi với tác ý chân chánh như vậy có được lợi ích gì (tuệ minh sát có thể phát sanh); và nếu không thay đổi oai nghi thì sao (phiền não sẽ lẻn vào). Thông thường, hành giả sơ cơ không biết được lý do của việc thay đổi oai nghi. Họ nghĩ rằng họ muốn thay đổi oai nghi, trong khi sự thực là khổ buộc phải thay đổi. Khi hiểu được sự thực đó và thường xuyên quán sát nó, hành giả sẽ nhận ra khổ, đồng thời thấy ra rằng, oai nghi mới cũng chẳng khác gì hơn oai nghi cũ. Như vậy tham sẽ không phát sanh với oai nghi mới và sân cũng sẽ không khởi lên đối với oai nghi cũ. Điều này dẫn đến trí tuệ thấy rõ rằng tất cả Danh-Sắc đều nằm ngoài sự kiểm soát, chúng không có tự ngã — đây là thực tánh pháp (sabhāva).

When sabhava is realized, a sense of urgency (samvega) will occur, and kilesa will be weakened. There will be more perseverance. Then, Satipatthana wisdom will be reached and will destroy abhijjha and domanassa in the Five Khandhas.

Khi thực tánh pháp đã được trực nhận, sự tinh tấn càng phát triển, và phiền não sẽ suy yếu. Lúc này, sự nỗ lực, kiên trì sẽ mạnh mẽ hơn, hành giả đạt đến trí tuệ Sātipaṭṭhāna (Niệm Xứ), tiêu diệt tham và sân trong năm uẩn.

3) Perception of Compactness (Ghanasanna) – Ý niệm về thật (Ghanasaññā):

Nguyên khối tưởng (ghanasañña)

Ghanasanna (compactness) of rupa and nama is sabhava-dhamma, or paramattha-dhamma―ultimate reality.

Nguyên khối tưởng (ghanasañña) của Danh và Sắc là thực tánh pháp (sabhāva-dhamma) hay pháp chân đế (paramattha-dhamma).

But even though it is true, it leads us to the wrong view of thinking that we are man or woman, or have a self. So, we then think rupa-nama is permanent and happy. Compactness thus hides the true state of the nature of rupa and nama―which is anatta.

Nhưng dù nó là thực như vậy, nó vẫn dẫn chúng ta đến tà kiến nghĩ rằng có một tự ngã, nên có thường và lạc nơi Danh-Sắc. Như vậy, nguyên khối tưởng đã che khuất thực tánh của Danh-Sắc, vốn là vô ngã (anatta).

So, the practitioner must have good “yoniso” in order to separate rupa and nama, so they don’t appear to be functioning as a single unit. Without “yoniso” we won’t know which is rupa and which is nama. Also, that the various rupas are different: sitting rupa is different from standing rupa, standing is different from walking rupa, etc.

Do đó, hành giả cần phải có tác ý chân chánh để tách bạch Danh và Sắc, nhờ vậy chấm dứt ảo tưởng chúng hoạt động như một thực thể duy nhất. Không có tác ý chân chánh, chúng ta sẽ không biết cái nào là Danh, cái nào là sắc. Hơn nữa, các Sắc cũng khác biệt nhau, sắc ngồi khác sắc đứng, sắc đứng khác sắc đi, v.v…

Six Vipassana bhumi (foundation, groundwork) are useful for seeing separation of rupa and nama. These are:

1) Five Khandhas

2) Twelve Ayatanas

3) Eighteen elements (dhatu)

4) Twenty-two Indriyas

5) Four Noble Truths

6) Twelve Paticcasamuppada (Dependent Origination)

Sáu lãnh vựcminh sát (vipassanā bhūmi) rất hữu ích cho việc nhận ra sự tách biệt của Danh và Sắc là Năm Uẩn (khandha), 12 Xứ (ayatana), 18 Giới (dhātu), 22 Quyền (indriya), Tứ Thánh Đế (Ariyasacca), Thập Nhị Nhân Duyên (paticcasamuppāda).

For example, under the Five Khandhas, we can see that rupa khandha is sitting, but it is vinnana-khandha that knows (with three cetasikas ― vedana, sanna, sankhara) [1] that rupa-khandha is sitting. Thus, we can see clearly the separation of rupa and nama (vinnana).

Chẳng hạn, với Ngũ Uẩn, chúng ta có thể thấy rằng sắc uẩn (rūpakhandha) đang ngồi, và chính thức uẩn (viññānakhandha) biết rằng sắc uẩn đang ngồi (với ba tâm sở là thọ, tưởng và hành). Như vậy, chúng ta có thể thấy rõ sự tách biệt của Danh và Sắc.

The practice to see through ghanasanna is the same as that for observing rupa and nama, (no special attempt is made to separate the two). The practitioner, however, should know that the nama that knows sitting rupa and the nama that knows standing rupa is not the same nama. And even the rupa that sits is not the same as the rupa that stands. So, the practice is done in the usual way until the wrong view created by ghanasanna is destroyed. As with seeing through continuity to impermanence and seeing through the postures that hide suffering, the practice to see through ghanasanna is the same; nothing more than observing rupa and nama and knowing which is which. Elimination of the false view that ghanasanna creates will lead to the 1st yana, nama-rupa-paricchedanana, or mind-matter determination (which is ditthivisuddhi―purity of understanding and insight). If the 1st yana is not reached, then progress to subsequent yanas can’t be made.

Việc thực hành để thấy rõ bản chất của nguyên khối tưởng cũng giống như việc thực hành để quán sát Danh và Sắc (không nên cố tình tách rời hai việc ấy). Tuy nhiên, hành giả cần phải hiểu rằng, danh biết sắc ngồi và danh biết sắc đứng không phải là một. Và thậm chí, “sắc” khi ngồi cũng không phải là “sắc” khi đứng. Việc thực hành cứ kiên trì như vậy cho đến khi tà kiến do nguyên khối tưởng tạo ra bị hủy diệt. Việc thấu suốt tương tục tính thực chất là vô thường và thấy rõ nguyên nhân sự thay đổi oai nghi chính là khổ, cũng giống như viêïc thực hành để thấy rõ nguyên khối tưởng vậy; không có gì khác hơn là quán Danh-Sắc để chúng được thấy, được tách bạch một cách rõ ràng. Sự diệt trừ tà kiến do nguyên khối tưởng tạo ra sẽ dẫn đến Tuệ thứ nhất — Tuệ Phân Biệt Danh-Sắc (Nāma–rūpa-paricchedañāṇa). Đây cũng là Kiến tịnh — Diṭṭhivisudhi — theo bảy cấp độ thanh tịnh. Nếu tuệ thứ nhất không đạt được thì các Tuệ tiếp theo cũng không thể dạt được.

The practice to see through the conditions that hide the Three Characteristics does not have to succeed with all three. It is only necessary to realize one characteristic. If you see through what hides anicca, for example, you will realize dukkha and anatta.

Việc thực hành để thấu triệt các điều kiện che án Tam Tướng, không cần phải kế tụccả ba, chỉ cần nhận ra một tướng là đủ. Nếu bạn thấy rõ cái gì che án vô thường, bạn cũng sẽ thấy rõ khổ và vô ngã.

[1] Here, vedana, sanna, or sankhara (usually, khandhas) are functioning as cetasikas, or mental properties, which go into making up the vinnanakhandha.

Sources:

Tài liệu tham khảo:

- https://tienvnguyen.net/images/file/Ek9kQjfF1wgQANp7/minhsattutap.pdf

- https://www.vipassanadhura.com/PDF/vipassanabhavana.pdf

- https://www.budsas.org/uni/u-gtmst/gtmst-11.htm

- https://theravada.vn/minh-sat-tu-tap-chuong-xi-nhan-duyen-che-an-tam-tuong/

- Photo 2: https://www.slideshare.net/bugstan/buddhism-for-you-lesson-05the-triple-gempart-2

- Photo 2a: http://evdhamma.org/index.php/dharma/dharma-lessons/item/1074-tam-phap-an-song-ngu

- Photo 3: https://www.thedailymeditation.com/body-scan-meditation-3

- http://bhoffert.faculty.noctrl.edu/RELG100/026.ContemporaryBuddhism.html